THE LOVELY BUTTERFLIES OF THE PHILIPPINES.

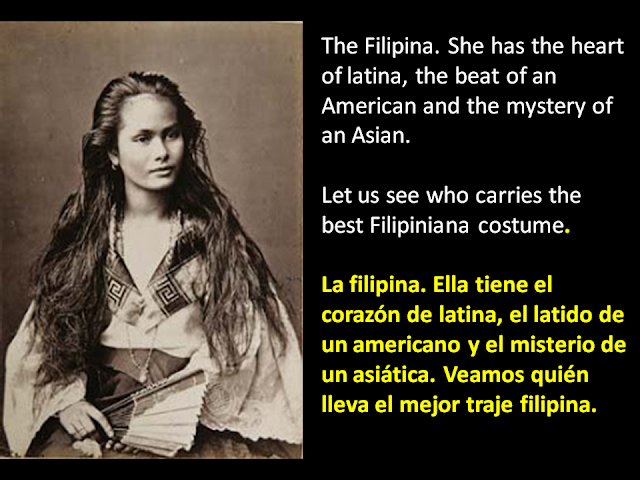

In our country, our women in their national costume are as lovely as the butterflies, aristocratic they may look.

The “baro’t saya” ( blouse and skirt) which were made from stiff and sheer materials on loose top with well-pronounced bell sleeves made from handloom textiles, mostly starched, to make them stylishly stiff. The kind of material used was dependent on what the status a woman was in society. The finest pineapple fiber called piña was for the affluent and high society ( called the insulares) while the rough banana fiber called “abaca” with fabric called “sinamay” was for the peasants ( called the peninsulares). This was apparent in Iloilo, the textile capital of the Philippines during the Spanish period.

The dress came with a triangular “pañuelo” (handkerchief ) or huge tusseled “Manton de Manila” scarf worn over the shoulder, and a “tapis “ ( a rectangular fabric) wrapped around the waist. The sweeping mermaid shaped skirts called “serpentina ” were made of cotton in handwoven patterns of stripes or checks.

.

For 300 years, the Filipiniana barely evolved until the Americans came for 50 years. The bell sleeves were flattened to become the signature butterfly sleeves of the “terno” so they could be detached and kept in wooden chests called “baul.” I remember my grandmother ( or "abuela" in Spanish for grandmother and her "primas" ( cousins) when the "muchacha" ( Ilonggo for house helpers) delicatelty pinned the butterfly sleeves on their "kimona"( saddle shaped) "baro" top. So to conclude, the bell sleeves when removed from the "baul" became flat, and when worn looked like butterfly wings! The "baro" were never washed because of the undergarment called "camisola" made them clean anyway. So they just went back to the "baul" flattened as thin as paper.

.

For 300 years, the Filipiniana barely evolved until the Americans came for 50 years. The bell sleeves were flattened to become the signature butterfly sleeves of the “terno” so they could be detached and kept in wooden chests called “baul.” I remember my grandmother ( or "abuela" in Spanish for grandmother and her "primas" ( cousins) when the "muchacha" ( Ilonggo for house helpers) delicatelty pinned the butterfly sleeves on their "kimona"( saddle shaped) "baro" top. So to conclude, the bell sleeves when removed from the "baul" became flat, and when worn looked like butterfly wings! The "baro" were never washed because of the undergarment called "camisola" made them clean anyway. So they just went back to the "baul" flattened as thin as paper.

The influence of America transformed the national costume into body hugging silhouettes with stylish almost like Hollywood style draping and the use of modern textiles like chiffon and synthetics as well as three-dimensional decorations like flower appliqués.

They were embellished with exquisite needleworks such as “callado” ( fret work embroideries), intricate beadworks until recently handpaintings or mix media decorations. Accessories came in the forms of “abanicos”( fans), “payong” ( umbrellas), “sombreros ( hats), “panyo”( hankies) , “baston” ( cane) and “filigrana” ( gold antique jewelry).

The distinct Filipino style is known to be the “ fondness for anything sheer” with the top garment so revealing to show the undergarment “camisola.” This sheerness is also found in the Filipino Spanish houses in “ventanillas” ( cut-outs), “barandillas” ( balusters) , “senefas “ ( fretworks) and capiz shell windows all transparent or punctured for see throughs.

It is said that one of the most elegant national costumes in the world is that of the Philippines with its unique and distinct BUTTERFLY SLEEVES.

Aristocratic they look. As flambouyant as the butterflies could be.

Escuela teaches the classical way to construct a terno.